On January 20, 2025, shortly after his inauguration, President Trump signed an executive order to withdraw the United States a second time from the 2015 Paris Agreement, an international treaty on climate change mitigation, adaptation, and finance. This is another high-level example of how we humans are incapable to act in the face of overwhelming evidence and the prospect of literally apocalyptical outcomes regarding our very existence: higher temperatures, increased health risks, rising sea levels, increased likelihood of extreme weathers like storms, floods, or droughts, species loss, famines, and the mass displacement of people.

Observing this incapacity to act decisively combined with year-after-year records in global temperatures and a clear upward trend of “Billion-Dollar Disaster Events” (among many other such things), I cannot help but making the following comparison – one, which is not very flattering for our species of so-called wise men: in the end, we may not be at all so different from brainless single-celled organisms which we routinely observe in lab experiments. Let me elaborate.

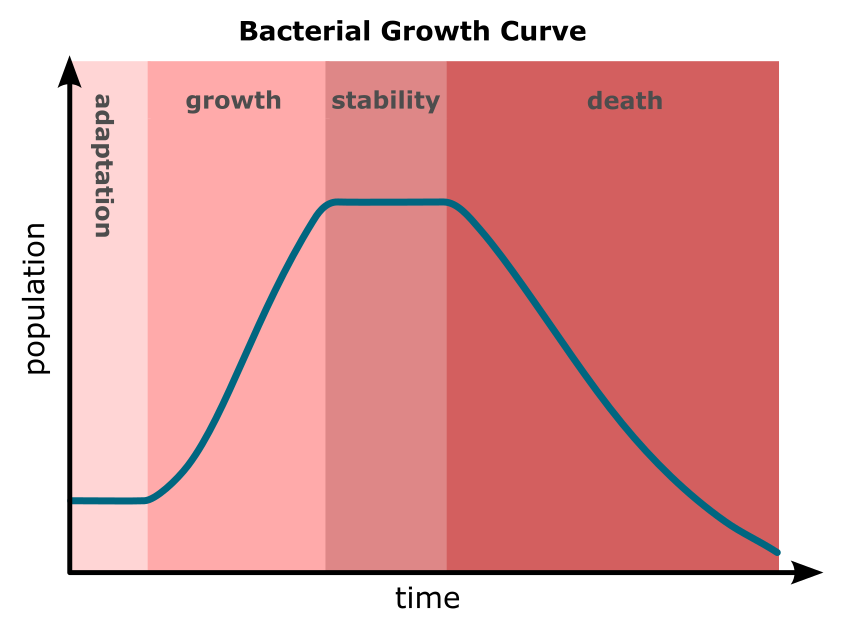

The chart below shows a stylised “bacterial growth curve“: the solid line sketches the population size (vertical axis) of a simple organism, like a colony of bacteria, in an enclosed environment (often a Petri dish) as time passes (horizontal axis). Left to its own devices, the colony’s population size goes through four phases: adaptation to the environment, rapid growth (more bacteria are generated than die in a unit of time, like hours), stability (an equal number of bacteria emerge and die), and finally a death phase during which the colony may die out.

Key parameters which determine the growth but also the subsequent decline of the bacterial population are temperature, the amount of nutrients available, and the concentration of metabolic waste produced by the bacteria during their lives.

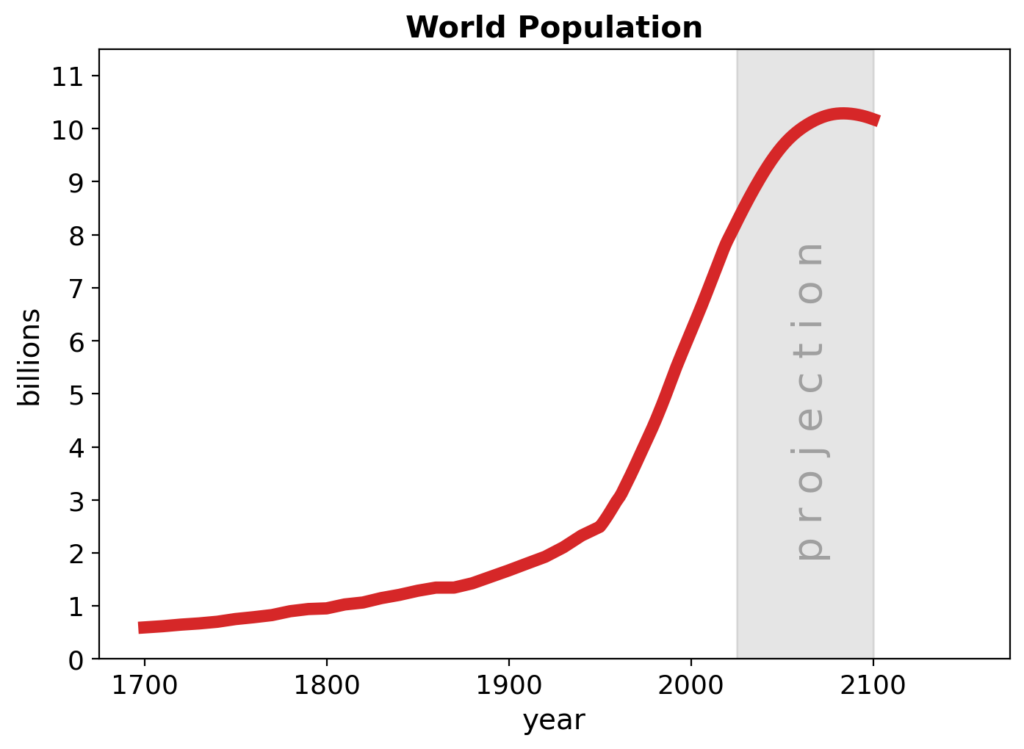

Let’s look at the human case. The next chart below shows the global human population between 1700 and 2100 (source). The grey area corresponds to the medium-fertility scenario of the United Nations World Population Prospects. I cannot help but to think that there is a striking resemblance between the bacterial case and our own development. We may be said to live through similar phases.

From 1700 until about 1950 we “adapted to our environment”. At the end of this period we figured out how to escape the Malthusian trap by producing enough food to sustain rapid population growth. Note that this adaptation phase lasted much longer than shown on the chart, namely from the beginning of our species some 300.000 years ago until the emergence of Elvis Presley in the 1950s.

The rapid growth phase lasts, or will last based on the shown projection, from 1950 until about 2050. The shortness of this phase compared to the previous is remarkable. It demonstrates what rapid technological advancement, and the subsequent population growth can achieve once we got the hack of it. However, we also see in the above chart that the subsequent stability phase may be shorter still, and be followed by decline, which nature we can only guess at the current point in time.

We have made analogies between bacterial and human growth patterns. What about the factors influencing both? We said that important factors for microbial growth are temperature, nutrients, and waste products. Arguably, these map well into factors playing key roles in our habitat Earth: air or water temperatures, the availability and quality of natural resources, and the widespread pollution of the planet.

Each analogy only goes so far. So, where does this here fail? A key factor driving human population growth is fertility. This also was a major input to the human population projection by the United Nations (grey area in the second chart). It seems a universal law in human development that fertility declines as societies advance. That is, people have fewer babies as they get richer. Multiple advanced economies already have birth rates below the replacement level to stabilise the population size in the absence of international migration.

This means that the human population may naturally shrink as we become richer by having less children compared to those who die. If happening on a global level, this will be bad news for the economic and governance models we currently operate. For example, who will pay all the needed pensions? But, such a scenario may keep us away from planetary boundaries, beyond which our Earth system may become unstable – again, with likely catastrophic consequences. More than bad news is then that the majority of such boundaries may have been transgressed already ….

As such, I don’t think that the analogy between our own existence on a rock flying through space and that of a colony of micro-organisms in a lab is too far-fetched. Realising this may even be helpful, especially it may be humbling. Some may find such a comparison to brainless creatures, which die in their own shit, insulting. However, think again, our ignorance to recognise the urgency of the situation and our incapacity to act in a globally coordinated way may at the end diminish our intellect to net-zero. If so, we will face the same demise as our brainless ancestors in the Petri dish.

Leave a Reply