Content warning: this post mentions rape and suicide. Also note the atheist premise of the blog. Please leave any comments below or send them to input@ponderer.io.

The first and maybe the only uncontested thing anyone can claim ownership of is their body. Absent the viable option to upload your consciousness to some form of a metaverse, your body hosting your mind constitutes you. Your body is and belongs to you. However, there still are plenty of restrictions on what you are allowed to do freely with your own body, particularly concerning your rights to reproductive autonomy, sexual activity, the consumption of psycho-active substances, and ending your life.

I argue that there are no reasons why these activities, which only concern yourself, should be forbidden or stigmatised. However, I do take concerns into account, and I will discuss two types of reasons for restricting personal rights: (A) your rights end where they would infringe the rights of somebody else, a negative Golden Rule type restriction. (B) Your actions would likely incur a cost on others deemed unacceptably high. The first is a logical restriction, as the rights of everyone need to be mutually compatible if we all shall have the same rights.

The second is based on the observation that almost any individual heavily relies on a functioning society for their livelihood. However, the argument of societal costs brings one into normative territory, where it’s about opinion rather than logic or facts. Therefore, any argument restricting individual rights based on societal needs must pass a high mark.

Let’s go one-by-one.

1. Life: the right to reproductive autonomy

As a man, I regularly feel ashamed about the indignities women need to endure up to the present day, even in so-called ‘advanced societies’. A major one is the right to and the access to reproductive health services. While some arguments, also apply to the access to fertility treatment, I will focus on abortion here.

Included in economically developed places, like the United States, we still debate if a woman has the right to decide by herself if she wants to get a child once pregnant (for whatever reason). For comparison, we are content to kill sentient animals by the hundreds of millions. But, when a certain bunch of cells is involved, some people lose it prescribing others how they have to live their lives.

By concern (A), the (prospective) mother’s rights may end where the (prospective) child’s rights begin. However, do we have a human at the beginning of a pregnancy? I strongly argue that not. If you ask me, a human, and its life, which ought to have rights for protection, starts from the moment they could live (with technical help) a life of their own.

Looking at data on the matter, preterm babies before the 22nd week of pregnancy have a very low survival chance, while most abortions would happen way before this point. As such, I see wanting to protect a bunch of human cells akin to wanting to protect the sperm of a man’s ejaculation. While fundamentalist religious groups indeed may want to do this by prohibiting masturbation, the vast majority of people plainly doesn’t.

The norm adopted by many European countries to allow and provide access to safe abortion roughly within the first trimester of pregnancy sounds like a reasonable approach. This could serve as an example for other places to progress. Additionally, there will be exceptions or extensions where a woman’s health is at risk or where a pregnancy is due to rape among other reasons.

Beyond this point, I am convinced that much of the opposition to abortion is driven by patriarchic legacies, or the male tradition of control over women. The simple argument holds that abortion would be considered a basic right if men could get pregnant. As such, a major argument against abortion is not one about protecting life, but rather one of protecting might.

2. Sex: f*** whom you fancy if they consent

According to the Human Dignity Trust (accessed 1 Jan 2025), “63 jurisdictions criminalise private, consensual, same-sex sexual activity. The majority of these jurisdictions explicitly criminalise sex between men via ‘sodomy’, ‘buggery’ and ‘unnatural offences’ laws. Almost half of them are Commonwealth jurisdictions.”

I find this seriously impressive. On the one hand, nobody’s rights are being violated when humans in any configuration are having sex, presumably consenting and in private spaces as stated above. On the other hand, being able to live out one’s sexuality is an important aspect of mental well-being.

Gay men are somewhat more discriminated against legally (globally) compared to lesbian women among other categories. However, considering heterosexual folks, we have yet another gender-gap favouring men. For instance, in most cultures, the image of a woman having many (or just more than one) sexual partners is definitely worse compared to that of a man with multiple opposite-sex partners. He may even be hailed for his manliness.

More generally, women face larger challenges to live out their sexual desires. For example, most porn is plainly made for men, and often unrealistic. So I think it important to have more of women’s voices heard on the topic. Good examples, unrelated to this blog, are books like Gillian Anderson’s “Want“, podcasts like “Adventures From the Bedrooms of African Women” by Ghanaian writers Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah and Malaka Grant, or contemporary sex-ed platforms like OMGYES.

Like for abortion, I believe that this imbalance is partly driven by a desire for male control over women, but, and that’s interesting, also by a feeling of male insecurity and fragility. Many men actually consider themselves ‘unsuccessful’ sexually, leading to extreme subcultures like the ‘incels‘ among others.

Global prudishness has complex historical and cultural roots. However, it is at unacceptably high levels given where we are now. So, let people f*** whom they want to if consensual (counter-argument A). Also, humanity is not at any risk of dying out if sex is free but ‘unproductive’ (counter-argument B). The rest of the natural world may actually be grateful for having less (or even no) humans around!

3. Drugs: let people get high and be happy

The “war on drugs”, resources thrown at inhibiting and penalising the production, sale, and consumption of a wide range of psycho-active substances is a massive white elephant.

The use of drugs to alter your state of consciousness is a constant throughout cultures and history. This means two things. One, people derive positive utility from it. It makes them feel better or helps them to achieve something which they otherwise could not. Two, there always will be demand for drugs. As such, there always will be the supply and markets for drugs, no matter what we do against them.

While some drugs are freely available in most parts of the world (alcohol and tobacco) others are legally restricted to degrees varying by substance, location, and time. That is, in a highly inconsistent manner. I argue here that (almost) all drugs should be legal as a matter of personal right. This would alleviate many social, health, and economic problems. But let’s start with the two main reasons given against the legalisation of drugs.

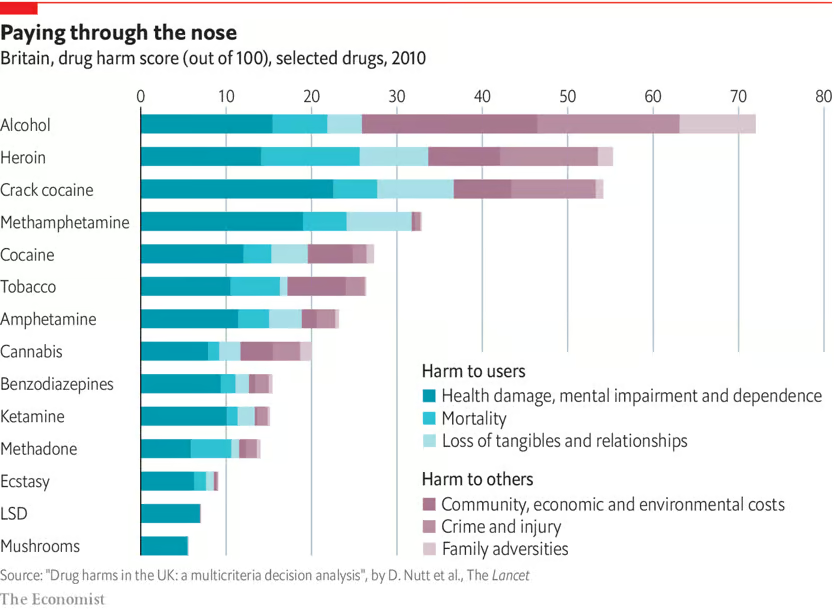

Reason 1: Health concerns. This can either be individual consequences, like addiction and self-harm (because we just can’t manage), or subsequent costs to society like crime or family breakdown (counter-argument B). The below chart (source) puts the harm potential of different drugs into perspective.

We see that alcohol is the most harmful drug. This is partly due to its wide availability and use. Furthermore, what are sometimes considered “party drugs” (what an infantile name!), like ecstasy (MDMA), LSD, or psilocybin (magic mushrooms), are currently being investigated for therapeutic uses, like for the treatment of trauma and addiction (from the UK Parliament). And yes, we are trying to use bad (forbidden) drugs to deal with the consequences of managing the good drugs (alcohol and tobacco).

We see that the harm potential of psychedelics (LSD and mushrooms in the above chart) is benign to their users and practically non-existent to non-users. Two reasons for this are the following: One, it is practically impossible to overdose with them. You would need to consume somewhere between 1-2kg of dried mushrooms to bring you into dangerous territory. Good luck with that! And two, they have low addiction potential.

Upon legalisation, there will be changes to the above chart as consumption patterns change. Do we know something of such changes? Yes, we do. We have one long-run experiment of the largely positive or benign effects of wide-spread drug decriminalisation (different from legalisation!): In 2001, Portugal decriminalised the personal possession of all drugs as part of a wider re-orientation of policy towards a health-led approach. And? Nothing crazy happened. The worst outcomes (drug-related death), fell and stayed consistently below the EU average among other consequences.

Reason 2: Support of organised crime. It is true that drug demand in richer regions (North America or the EU) partially drives drug production in often poorer regions like South America in the case of cocaine. The Mayor of London once said that “middle-class parties” fuel organised crime.

It also is true that organised crime causes tremendous damage and should not be supported. However, the argument about drugs and organised crime gets cause and effect the wrong way round. As we said, drug demand will always be there, and organised crime only reacts to market forces created by this demand and drug prohibition. Organised crime just takes the money left on the table. And these moneys can be huge in the case of drugs as we all know from the opulent drug dramas and thriller which often have a real story at the core.

So, given that a market for drugs will always be there and of considerably size, what’s the wisest thing to do from a public health and crime prevention perspective?? Exactly, provide those drugs under reasonable conditions.

Reasonable here means (1) ending the market for organised crime thereby creating massive tax income for stretched public services, especially health, (2) providing quality substances and utensils minimising the risk of health issues related to drug consumption, and (3) the protection of vulnerable groups in the population, such as children and teenagers (as is common for alcohol), through restrictions, education, and health measures.

From both, the personal-freedom and the public policy perspective, it’s a no-brainer to exploit this win-win situation of happy highs, better health outcomes, lower crime, and better public finances.

A final note on ‘hard drugs’ like synthetic opioids (like fentanyl) or crack cocaine. Many describe their recent spread and impact like that of an epidemic with no effective public health response so far. As such, this development could serve as ground for a knee-jerk reaction condemning any drug liberalisation. However, this all happened under a strict regime of prohibition, which makes any public health response doubly difficult because of the stigma and possible prosecution consumers face.

4. Death: the right to die

The movie Bird Box is a simple yet captivating thriller: unspecified entities appear on Earth, and almost everybody seeing them is immediately driven to suicide. This leads to horrifying and creative ways people ending their lives quickly en masse, ultimately leading to the collapse of modern society. The main story is then a standard survival tale in a post-apocalyptic world.

Focusing on the suicides in the movie, what is wrong with them? Right, they are not ‘consensual’. Apart from the minority of people who see the entities, and rather support them in making others see them, and subsequently kill themselves, people have no freedom whatsoever to ponder and freely decide on the act of suicide. That is, these are rather victims of murder.

However, if the option of a free decision were on the table, the mere act of killing oneself is not wrong in itself. Everybody owns there body, and is free to decide themselves whether they want to make it stop working, thereby killing themselves. To be clear, I do not advocate or encourage people to commit suicide here. This often has considerable costs, especially emotionally on your family and friend. If you struggle with suicidal thoughts, seek help.

The point is one of personal freedom about the right to your body, the main theme of this post. This is nowadays mostly relevant in aging societies with improved health care, where there is an increased risk that a considerable number of people spent a considerable amount of their time suffering.

This brings us to the discussion about assisted dying. That is, government-sanctioned access to medical services to end one’s life with certainty and in a humane way. Such assisted suicide is available under varying conditions to a lower percentage fraction of the global population, almost exclusively in developed countries, while the possibility of the refusal of treatment when terminally ill is available to more people (the right to die).

This means, that humanity still has a long way to go in providing access to this form of end-of-life care. As for the legalisation of drugs, a key concern is the protection of vulnerable groups. That is, any decision of dying and access to assistance must be coupled to the person in question having a clear mind and that such a decision is taken without coercion. I strongly believe that creating frameworks fulfilling these conditions is possible. For instance, I have not heard of major scandals or wide-spread misuse happening in countries where assisted suicide is available, partly for decades, such as in Switzerland.

The next question is then who should be eligible to qualify for access to assisted dying. This question is highly complex, and I don’t feel comfortable to provide a concrete view. My general suggestion would be to make it available to persons who have severe health conditions, which cause a large degree of suffering and which are unlikely to be cured within a reasonable time frame (or ever), or the terminally ill with a short remaining lifespan.

While everybody has the right to die, I would not provide government-sanctioned services to healthy people. My thinking is here that of most vets who would (and should) refuse to euthanise healthy animals in most circumstances. Those resources could be spent otherwise, such that the burden of action falls onto healthy individuals if they wish to go.

Wrapping up

There is one (major) personal right to the own body which I did not list yet: the right to your appearance, like your hair style, or how you dress or decorate your body. The reason for this is that, while also not yet perfect, we made tremendous progress here. In many places in the not-too-distant past, looks which would not be noticed nowadays, like men with long hair or women in trousers, caused serious stirs, or people faced discrimination and partially legal restrictions.

I am cautiously hopeful that, in the not-too-distant future, we will look back with a similarly benign view, potentially somewhat amused, on the personal rights on life, sex, drugs, and death. The world would be a better place.

The world being a better place overall would mean that we on average live better lives if the personal freedoms discussed here were widely granted. However, some individuals who disagree with such liberalisations, may feel that their welfare is diminished because they disagree, maybe because they want to have all of the world be in a certain way.

There is a simple counter-argument to this. This is the reverse version of (A) from the beginning: if you are not personally affected by someone else’s behaviour, just mind your own business.

The short version of this, and maybe the strongest argument in favour of personal rights, is: live and let live!

Leave a Reply