Here is the recent case. It’s a global pandemic of a potentially deadly virus which can spread through air. Wearing a facemask covering your mouth and nose can suppress transmission protecting you, if you are not sick, or others, if you are. However, you find it uncomfortable breathing with this thing in your face, think you look silly, don’t think that you are infected, and that you would not be scathed by an infection anyway. So you decide not to wear a mask when taking the subway to work.

The above is a classic examples of conflicts between an individual’s wellbeing or preferences and that of others in society. These discussions had been prevalent during the recent coronavirus pandemic. However, as I want to argue in this article, the perceived tensions between individual and collective benefits are at the heart of many fundamental social, political and economic conflicts, and that we should discuss those more explicitly to better solve our conflicts – big or small. Here is how to.

Society consists of groups of individuals, such as families, local communities, firms, cities, countries, etc. Groups mostly deliver some net benefits to its members, like resources, protection, or opportunities. However, individual members need to adhere to some rules or have to give up something to allow the group to operate as a bigger entity. At the same time, the individual may have relatively little say about such rules, costs, or even membership of a group in the first place. The resulting trade-offs lead to tensions between a group and individual members. That is, between what are the interests and rights of the individuals within the group, versus those of the group over each member. To safeguard both the viability of the group (if it is worth it) and the rights of its members, these tensions need to be addressed.

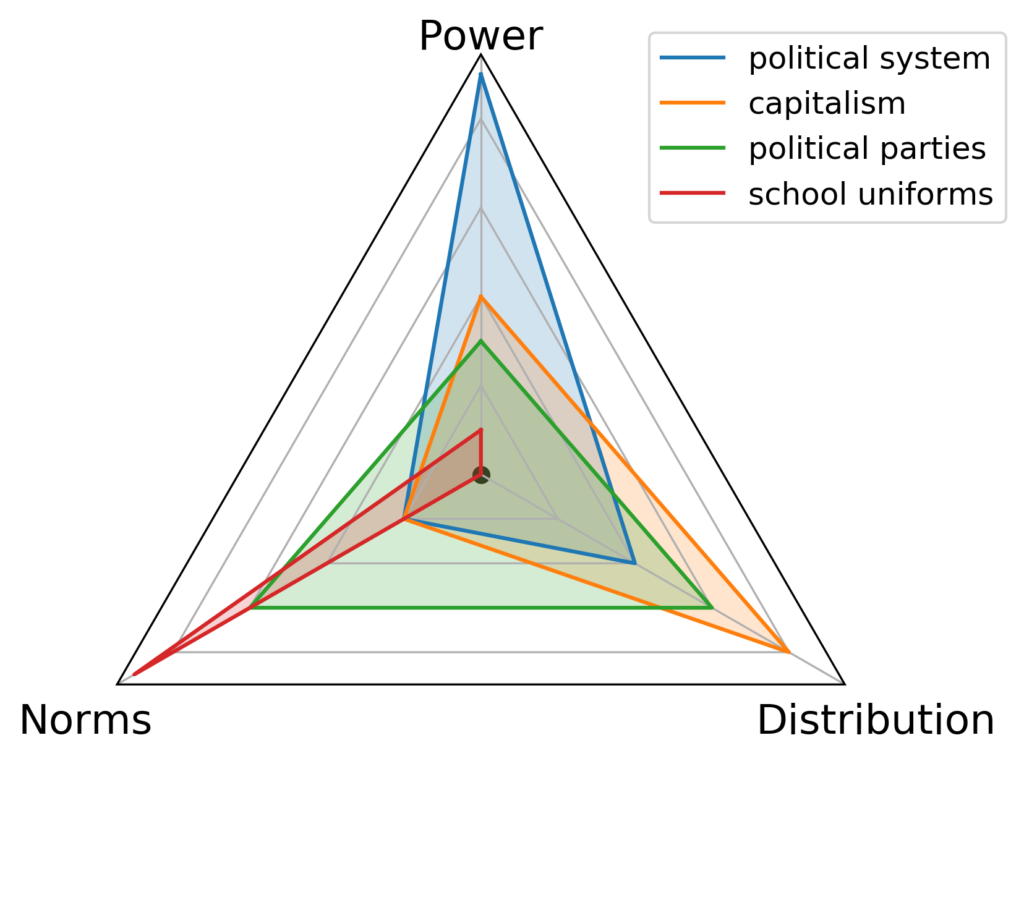

Taking an analytical view, group tensions often can be framed alongside three conflict dimensions: power, norms, and distribution. On the power spectrum, group decisions are being taken by a single person on the one end (autocracy or dictatorship), and by broad-based member decisions (democracy) on the other end. Norms mean the degree to which pluralism is accepted in terms of behaviour of group members. For example, does every pupil at a school has to wear the exact same uniform, or are fancy skirts for boys acceptable as well. Distribution relates to the degree that resources deployed or exploits received by the group should be shared more or less evenly across group members. For example, should all employees of a firm be paid the same independent of rank and task, or should the senior management receive all profits and the remaining staff be compensated at subsistence level?

The above offers an analytical framework for the analyse of individual-vs-group conflicts. I will first make some further explanations, and then view examples of group tensions through the lens of conflict dimensions. The important point, however, I want to make here is not whether you agree with how I frame problems, but that I believe it to be important that we talk more about tensions between individuals’ interests and that of society. How one frames problems may be less important, while the approach presented here I believe can be helpful to address them. So, let’s proceed and you judge later.

First, mostly only one or two conflict dimensions will be relevant for the analysis of a problem. For example, power or distributional aspects will be less relevant to the school dress code question. Second, group purpose is linked to the conflict dimensions. For example, if a company thinks that passion and long-term commitment from its employees is important to fulfil its mission, engagement and achievement of employees must somehow be rewarded, and there should be clear developing paths. More generally, our framework is positive, in the sense that it aims to facilitate objective discussions. It cannot, however, deliver answers straightaway. These will always be normative, where some preference is chosen over another, or a compromise between competing interests is found.

I will next show how some of the biggest divisions in society can easily be framed alongside our conflict dimensions, as can much smaller problems of everyday life. On power, the probably biggest challenge societies face is how they organise political decision making, i.e. the balance between autocracy and democracy. Today about half the world population lives in some form of democracy, and the majority of people has some electoral rights. Despite a recent retreat of democracy, these facts are astonishing, because about 200 years ago virtually everybody lived in autocracies.

Let’s look at capitalism, which is an economic system where, in its raw form, the means of productions are in private hands and the distribution of resources is handed to markets for goods, labour and financial capital. The principal dimension alongside which to evaluate group conflicts in capitalism, e.g. between firm owners and workers, is alongside the lines of distribution, such as wages vs profits. However, given the far-reaching consequences of the prevalent economic system in a society, especially political conflicts of power will also play a role, not least given concerns about inequality and ecological sustainability which both reach far beyond economic organisation.

Placing ourselves into an established democracy, e.g. in Europe or North America, where there is a broad acceptance of the prevalent system of managing power, the main political fault lines are along the social normative, e.g. “culture wars”, and the distributional conflict dimensions. The positions of differing (moderate) political parties can then mostly evaluated along those lines. Centre-left parties nowadays are often socially progressive (emphasising the rights of the individual) and economically inclusive (all stakeholders, especially workers, should benefit from economic activities, and there should be a strong social safety net when things go wrong). Centre-right parties often take the opposing positions where social change should be managed carefully (hence the name conservatives) and economic profits should be allocated by market principles, while the individual is mostly responsible for their own sake.

Using our three conflict dimensions, the examples of political leadership, capitalism, political orientation, and school uniforms, are summarised in Figure 1. This is a radar chart with three axes, one for each conflict dimension. Each shaded area represents one topic. The further out a triangle reaches along an axis the more important that dimension is for the analysis of conflicts related to that topic. This analysis can then serve as a first step to guide the discussion of related problems. Next, each major direction needs to be broken down along the spectrum of the group related group problems. It is this second step where normative arguments and finally judgement enter the process.

This then provides a “workflow” to analyse conflicts:

- Identify the important conflict dimensions: mostly one or two out of power, distribution and norms.

- Identify the relevant groups and stakeholders.

- Present positive and normative arguments along each dimension from (1) relevant to (2).

- See to find a workable solution based on (3). This solution will in most cases be based on normative judgement. This means that it is neither right nor wrong but aligns more or less with differing preferences.

The normative nature of step (4) is the tricky bit, as there is no clear guidance to how to end up with a good solution. This explains the difficulty of finding consensus for complex problems affecting large groups of people: It’s generally impossible to make everybody happy. Effective procedures with checks and balances, like civil society institutions in liberal democracies, can facilitate the decision process. Discussing these in more detail goes beyond the current post which only wants to suggest a way for looking at problems.

Let’s go back to our initial problem of whether to wear a face mask on public transport during the recent pandemic, and see how we could approach it with the framework we just developed. Debates in this realms could get very heated. For example, in Germany the clerk at a gas station was shot dead for trying to enforce mask mandates. Apart from providing structure, one goal of applying our framework is to take out such heat, and to create space for reasoning and compromise.

Here is how the problem could be addressed using our workflow.

Step 1: The problem is predominantly about social norms, so this is the only dimension we consider.

Step 2: Since health is a concern of everybody, the involved groups or stakeholders are quite broad, and can be said to be almost everybody in society.

Step 3: What are the arguments? Given the large group involved, there could be many, and one way to approach this is to list pro and cons on the side of the individual and of general society. One the one hand, facemasks protect the individual and, on the other hand, be inconvenient to carry or to violate one’s freedom of choice. The societal arguments could be that wearing a facemask protects others, i.e. protecting the health and economic resources of others, but also constitutes an economic and environmental cost.

Step 4: A strict cost-benefit analysis, i.e. where one puts monetary values at the different arguments is not feasible, because much of it is about preferences. This also is how this debate and its solutions have been handled differently in different parts of the world. Given that wearing facemasks, either when sick or to protect oneself, was already relatively common in East Asia, e.g. in Hong Kong from my own time living there, mask mandates or even social norms about wearing them did not constitute a big problem there. However, Western countries struggled somewhat more with finding common ground, while most of the debates were about personal preferences, less economic or environmental concerns. This again highlights the difficulty around finding a solution, because it often will be about normative judgement in the end.

A last comment before we conclude. The discussion so far was about individual-vs-group problems, i.e. intra-group conflicts. However, the approach here can in very much the same way also be applied to inter-group conflicts, i.e. when it is about the interests of one group versus those of another, for example in the current discussions about identify politics.

This brings us to the end of this rather long post. The messages I want people to take with them are that we should more clearly talk about group conflicts (intra or inter), and that these problems can be approached with the simple framework provided here, ultimately with the goal to take good decisions.

Leave a Reply